The latest story in the Design Life series.

Amuse Bouche: Rage Restaurant

Appetizer: The Frame Spider

Entree:

Ford Kharkey sat behind the wheel of his immaculate repair van, eyes scanning the road ahead. His assistant, Cleave, a lumpy nug of rich red and pink ground beef, sat shotgun, upright in a plastic tub secured by a metal O-ring lashed to the passenger seatbelt. Just south of Belle Glade on Florida 27, they drove in silence for a while, punctuated by the intermittent sounds of love bug splats and wipers against the windshield.

As nugs went, Cleave was the best repairmeat Ford had ever worked with, going 22 years back to his first gig with The Burbegeir Bumbger Corporation. Their first-generation stem-cell driven vending machine, the Forgottomanni.1000 Food Synthesizer, named for the co-inventor of sentient meat, Emilio Forgottomanni, brought BB’s patented Stemburger™ to every corner of our round Earth.

Ford and his first few partner nugs at BB witnessed history as it happened as they maintained those early machines. On the backs of their army of repairmen and repairmeats, BB’s synthesized burgers dominated the early market for stand-alone stem-cell driven vending.

The stemburger patty comprised a chimeric hybrid stem-line that weaved truffle-fed pork belly and wooly mammoth cheek into Wagyu ribeye. The 1000 series machines also stemmed all the finished dish components on the fly in its internal collider, from the lettuce to the catsup. A self-sustaining colony of licensed Frame Breadspiders even spun the buns.

The resultant flavour experience was irresistible to all but the most meat-loathing. As for the synthesized patty’s critical reception among the gourmanderatti, Padam Apaport, writing in the culinary trendsetting rag Füdz, conjured on their first bite their now-vernacular 4-star 10-word review:

“If fast food is a felony, then cuff my tongue.”

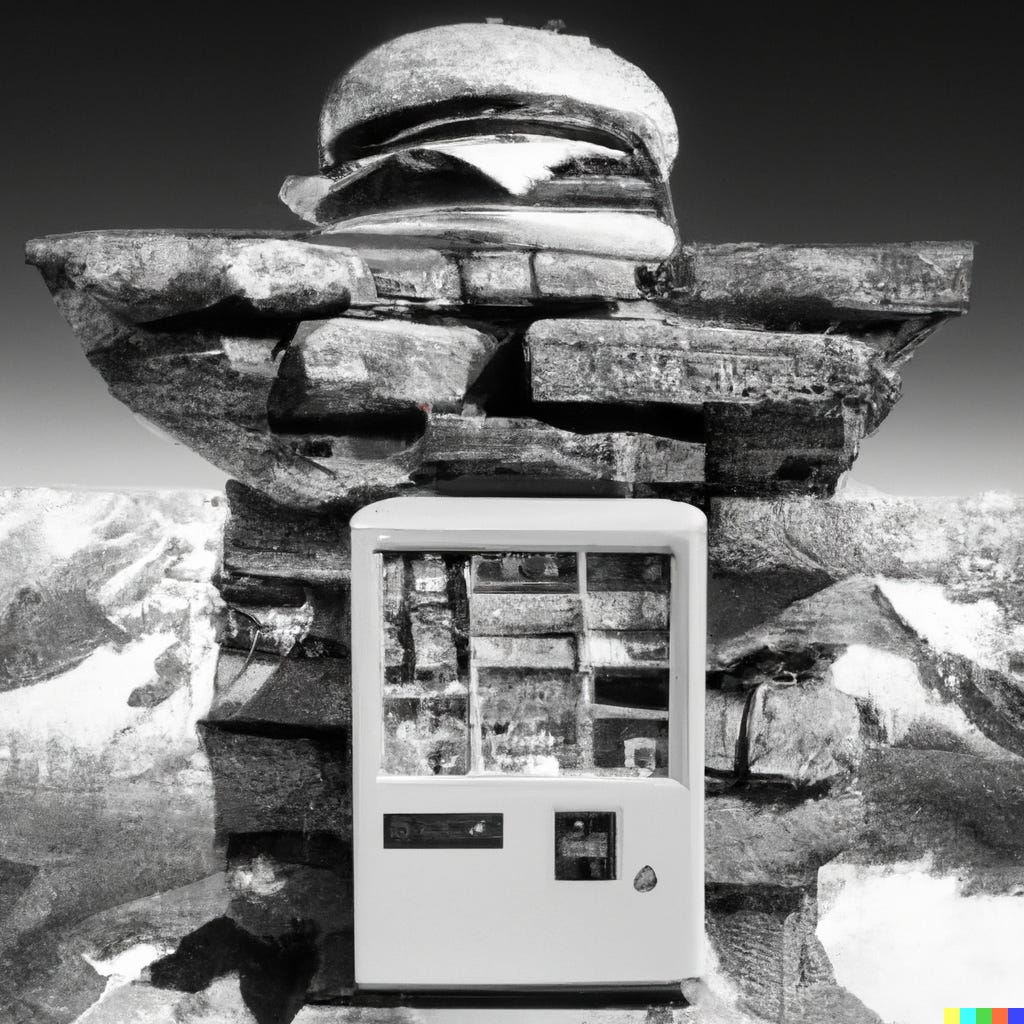

The company’s most far-flung stemburger machine was a modified original Forgottomanni.1000 that hummed along on Mount Everest for 18 years. Needing neither cow nor pasture, neither farmhouse nor slaughterhouse, the world’s most remote food synthesizer served up the juiciest burgers that side of Kathmandhu.

The C-Suite of Burbegeir Bumbger pushed hard to get their custom machine to Everest’s summit, building a special “lunar module” unit to withstand anything thrown at it by Mother Notsure at 8,848.86 meters. In anticipation of the climb, the first ads for the 1000 series even set the machine at the mountaintop.

The space-travel-ready stemvendor, however, did not make it higher than South Base Camp. As the project moved forward, repair nugs began to break down with altitude sickness, and underperform during testing. There was simply no way to respirate wads of repairmeat with enough oxygen to maintain their consciousness, let alone sentience, even halfway to the top. BB’s high-end food synthesizers couldn’t be serviced without functioning nugs, so the Forgottomanni never summited the mountain.

Still, South Base Camp was impressive enough. Associating the stemburger with a pinnacle of human achievement was brilliant marketing. A triumphant “base burger” photo on an OpenLife friend-of-friend feed is still an extreme travel influencer rite of passage. Turns out nobody doesn’t want a hamburger after they descend Mount Everest.

The early days of stemvendor repair were rife with risk and complication. Humans had difficulty maintaining some of the machine’s more nano-scale innards, and couldn’t get near the flame unit’s subatomic stem-cell collider without risking a quantum rupture of our universe’s gravitational glue. Most machines broke down and remained in states of disrepair soon after placement in the wild.

Opening the machines was a time and money suck for the BB Corporation. The simple solution was to fight meat with meat, so BB set about creating the “nug,” a sentient meat patty that could radio out to you what was going on in the stemvendor innards. The internal corporate effort was a perfect storm of operational efficiency and managerial acumen, and with the launch of the first nug, the stemvendor was ready for reality.

“Nugs — they can really sense the issues, solve problems,” BB’s founder Karl Bumbger told Füdz on the heels of the stemburger’s glowing review. The quotation appeared in an article that celebrated the company’s operational ingenuity, but also, amid some backlash on the telly, questioned the ethics of employing nugs that the magazine defined as “meat life with the intelligence level of children — essentially a child labor force.”

Bumbger was undeterred. “Look,” he said, “the smartest nugs — they talk to the other meat. Get a bead on the mood of an individual vending machine. It’s like we got unions, but with no dues.”

The true ethics issue, however, came when machine break-downs often necessitated a nug to negotiate a machine’s innards, going undercover, in a way, as a real burger. Childhood-level of intelligence or not, the sentient meat army employed by Bumbger was un-conscripted and coerced into battle. Essentially an indentured suicide mission force.

In their defense all those years ago, in that early era of thinking objects, beyond lack of durability, most newly sentient creatures like nugs were still gathering their individual and collective intelligence from their tasks and their mentors. Human repairmen needed to use every ounce of their creativity to keep burgers flowing from the machines, while also teaching their partner nugs how to think in a more human way. First-gen nugs tended to whine a lot, too, while demanding stress-relief kneading, making the car rides to repair jobs often interminable (and one-handed).

But as planned, through the years, nugs grew smarter and more trustworthy, and more adept than their human partners at traversing and diagnosing ever-more sophisticated remote food synthesizers. This growing symbiosis inspired close bonds between meat and man.

The relationship, however, was always colored by the possibility of sacrifice. Theirs was a very dangerous, dirty job.

Most vending issues were resolved ahead of the grill sector, but if an issue was in the flame unit, or in the subatomic collider (where stem cells were cultivated in response to customer input), to ferret out the solution, the nug would have to be cooked as a true patty.

Cleave was a latest-generation nug, having come into consciousness only a couple years earlier. He never complained, never made a mess, and most importantly, was sentient enough to hold a college-level conversation.

Some of his contemporary nugs only understood basic commands, and had no awareness or control of their emotions. Turns out wads of meat are lazy to the core, and self-improvement is not high on their priority list.

Cleave, though, used his down time to study, falling in love with the writings of existentialists, especially Albert Camus, whose words provided a salve to Cleave’s asphyxiating feelings of organic unmeaning.

“There is more to me than meats the rib-eye!” he would joke on the job, to merciless groans from fellow nugs. He saved deeper thoughts, however, for his inner voice. His favorite mantra was one he repeated softly to drift himself to sleep, I am absurd and beauty at once.

Back in the van, Cleave and Ford were on their last job of the day, a stemburger machine that had been acting up all week at a remote gas station in central Florida. Ford had tried his usual tricks to fix it over the company intranet, but nothing seemed to work. He had even called the manufacturing plant, but they had been less than helpful. So now, with the sun setting on the horizon, they were driving to the machine’s location, hoping to finally get it running again.

Cleave was quiet, as usual, but Ford could sense his partner’s apprehension. Fixing a stemburger machine was no easy task, especially when the problem seemed to be with the patty production process. A patty problem meant higher odds Cleave would need to crawl inside the machine.

Though Ford had been doing this job for over twenty years and had never failed a customer yet, Cleave’s confidence was tempered. That day, his mind became riddled with thoughts of his own existence. He kept wondering if every part of him, down into his deep nug, thought and felt, or if his consciousness was confined to the specific part of his being whose thoughts he could hear.

Finally, unable to contain his internal debate any longer, Cleave turned to Ford and asked, “Do you think every part of you thinks?”

Ford looked at him quizzically, unsure of how to respond. He had never considered the question before, and he wasn’t sure if he had a satisfactory answer. “Maybe,” he said after a moment. “But I make the choices.”

Cleave nodded, and calmed, if only for that Ford understood his question. He snapped back to the mission. Sentient and conceptual, he was still just a piece of meat, with a job to do.

As they pulled in to the service station, the faulty vending machine beckoned them from just outside to the left of the small convenience store. The machine was a standard model Manraaces AngusVision 2, with a glass front displaying burgers in process (“Red, Ready, Readiest!” its window decal read), and metal sides adorned with trompe l’œil ribbons of burger juices dripping from a BB OG into a bed of fries.

Ford opened the machine’s door and inspected the unit’s innards. The problem was obvious on first glance, a too-well-known issue. The stem-cells were going haywire in the collider, reading the burger output and customer epigenetics wrong, synthesizing patties too thick, causing the machine’s conveyor belt to jam. Ford pulled out his tools and got to work, and was quick to realize that they needed Cleave to push a few pounds of jammed meat out through the flame unit.

He turned to Cleave, who was watching him intently, analyzing each step of the process. “You’re the only one who can move the meat,” he nodded. “Code cordon bleu.”

Ford’s gravity was not lost on Cleave, whose eyes widened in slight shock. He took a long breath, in then out. “Code cordon bleu,” he repeated back, resigned to his fate. “It’s my time, then.”

Cleave took another deep breath. “Hey, tell me. Are there any other nugs like me, Ford?”

Ford thought about lying for a second, and telling Cleave he was the only highly sentient meat he’d ever known. In the end, however, preserving Cleave’s sense of individuality wasn’t company policy, or sound philosophy.

“Yes,” Ford said. “Every day, nugs like you help fix broken machines across the state.”

Cleave knew then that the meaning of his life was in sacrifice. He would go through the burger cooker. This was not his choice, but how he reacted was, so he leaned on his Camus and Jung. “It actually helps,” he put forward with a calm cadence, “to know I’m not the first or last. That other nugs will know of this calling. We are a continuum.”

Ford fired up the machine’s grilling function and placed Cleave on the conveyor grate. As Cleave glided deep into the machine and entered the flame chamber, he sizzled and popped, and Ford winced at the sounds.

“You’re not alone, buddy,” Ford offered, close to a whisper, as a mass of charred, jammed meat plunked out of the flame unit’s exposed exit pipe.

Ford had always felt a little guilty about cooking his partners, but it was necessary for the job. And his bosses at Manraaces (a division of War-Malt Superstores), the current remote food synthesis company he contracted with, assured him their latest nugs had no nerve endings, so they don’t feel pain.

It was true, in his last few years on this deploy, Ford not once heard a nug cry out in shock or fear — whether burned alive, crushed under a car wheel, or torn apart by stray dogs. Still, Ford remained haunted by how a few of his former nugs met their demise.

Once Cleave was cooked through, Ford took a few patties from the machine and placed them on the conveyor belt. They glided smoothly through the mechanism, and Ford sighed in relief.

Ford packed up his tools and closed the vending machine’s door. As he gassed up the van for the ride home, he could feel Cleave’s presence beside him. He flipped the pump nozzle’s hold-open clip in place, then shook himself from head to toe and side-to-side to exorcise his thoughts and spread some oxygen around his body.

And as he looked off into the deep swamp beyond the gas station, Ford felt enveloped by a warm sense of peace. He knew that the work he did was important, that it helped to keep the world turning. We keep the machines running, so the machines don’t run us, he thought, smiled and bowed his head.

Ford then lost himself in the singing of frogs and crickets, and the buzzing of love bugs around the station’s floodlights. In this peace, he surrendered to the serenity of the swamp.

Problem solved, Cleave, he thought to himself.

Find me also at https://westyreflector.net, and @westyreflector on all the popular platforms.